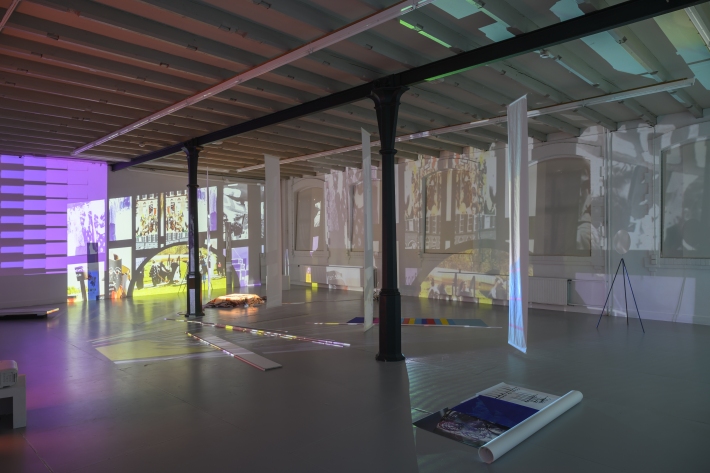

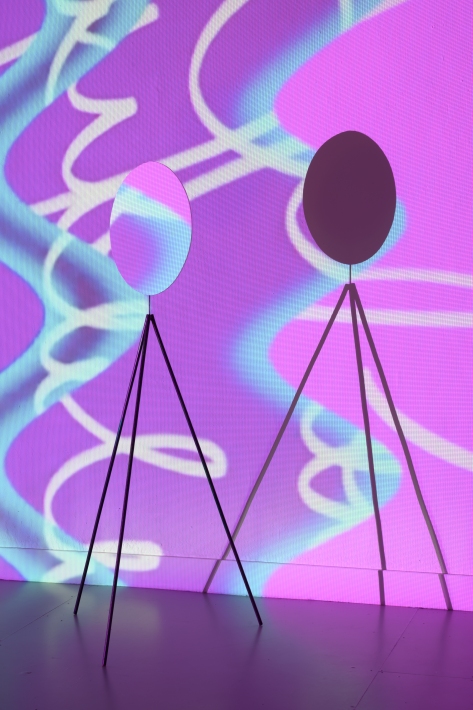

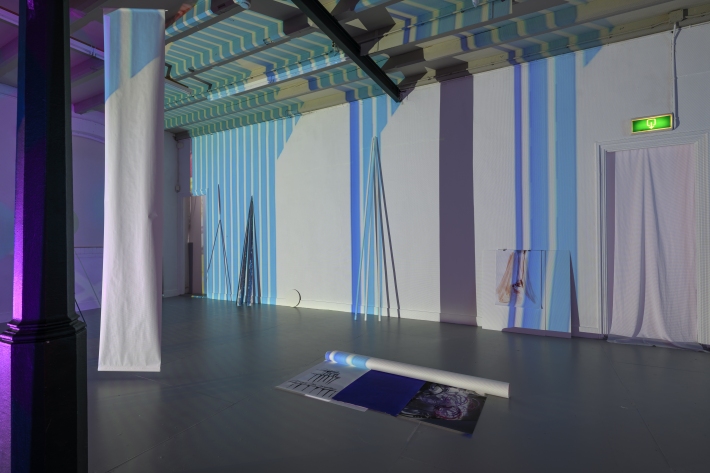

Mother Song, 2022

Site-specific installation; 2nd Floor

Part of the solo exhibition at Club Solo, Breda

Website information Club Solo:

https://clubsolo.nl/agenda/winekegartz/

Photo 1, 2, 3, 4, 5: Peter Cox

Photo 6: Dorrith van der Bijl

Photo 7: Wineke

Site-specific installation; 2nd Floor

Part of the solo exhibition at Club Solo, Breda

Website information Club Solo:

https://clubsolo.nl/agenda/winekegartz/

Photo 1, 2, 3, 4, 5: Peter Cox

Photo 6: Dorrith van der Bijl

Photo 7: Wineke

The site-specific installation Mother Song is specially made for the exhibition space on the Second Floor of Club Solo: The rhythmic spatial collage includes abstract fragments from the photo archive of Gartz' father and mother, especially from the period when Gartz' mothers Thea was part of the Vrouwen voor Vrede (The Women's Peace Movement). The group protested against nuclear weapons, and fought for peace and equality. Mother Song is a spiritual work about action, stillness and movement.

At the ground floor exhibition space, Gartz made The Way Home II, a new version of her video installation The Way Home I, which she made in 2008 at a former nuclear bunker (Safe, Dalfsen), and she reactivated in Club Solo.

See for photos of The Way Home II: https://www.winekegartz.com/works/The-Way-Home-II

Gartz' approach to the two spaces of Club Solo was, to make two contrasting spaces, with works which are complementary. Unlike the light and dynamic installation Mother Song at the upstairs gallery, the feeling at the Ground Floor exhibition room is dark and static, with a minimum of colour. The exhibition space has exactly the same plan, the same amount of windows and the same measurements as the upstairs space, but it is transformed into a dark, and disorienting place. Two installations The Way Home II and Open Water II, are carefully placed inside and outside of a designed walled space. The wall has a particular color grey on the inside, and staged light. Thin wooden laths reach the ceiling and form an inverted triangle. The void between collages, wooden panels, projections and architecture is just as important as the elements themselves. The totality is both comforting and uncomfortable. It moves between contemplation and disturbance, coldness and proximity, life and death. The trance-like soundtrack, an electronic track by composer Barbara Morgenstern, occasionally disrupts through a chaotic part, containing fragments of a popsong by Muse, with drums, electric guitars and a haunting voice.

At the ground floor exhibition space, Gartz made The Way Home II, a new version of her video installation The Way Home I, which she made in 2008 at a former nuclear bunker (Safe, Dalfsen), and she reactivated in Club Solo.

See for photos of The Way Home II: https://www.winekegartz.com/works/The-Way-Home-II

Gartz' approach to the two spaces of Club Solo was, to make two contrasting spaces, with works which are complementary. Unlike the light and dynamic installation Mother Song at the upstairs gallery, the feeling at the Ground Floor exhibition room is dark and static, with a minimum of colour. The exhibition space has exactly the same plan, the same amount of windows and the same measurements as the upstairs space, but it is transformed into a dark, and disorienting place. Two installations The Way Home II and Open Water II, are carefully placed inside and outside of a designed walled space. The wall has a particular color grey on the inside, and staged light. Thin wooden laths reach the ceiling and form an inverted triangle. The void between collages, wooden panels, projections and architecture is just as important as the elements themselves. The totality is both comforting and uncomfortable. It moves between contemplation and disturbance, coldness and proximity, life and death. The trance-like soundtrack, an electronic track by composer Barbara Morgenstern, occasionally disrupts through a chaotic part, containing fragments of a popsong by Muse, with drums, electric guitars and a haunting voice.